18 (2025), nr 2

s. 447–465

https://doi.org/10.56583/fs.2855

Licencja CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

ISSN: 1899-3109; eISSN: 2956-4085

Z PROBLEMATYKI LITERATUROZNAWCZEJ, KULTUROZNAWCZEJ, FILOZOFICZNEJ

LITERARY, CULTURAL, AND PHILOSOPHICAL ISSUES

Dr. habil. Krzysztof Jaskuła

The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin

e-mail: krzysztof.jaskula@kul.pl

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5292-4163

Angielski i maoryski – relacje bilateralne i fonologiczne interpretacje zapożyczeń

Summary

This paper concerns linguistic interactions between English and Māori as another example of loanword adaptation. As the prevalent language, English began to influence Māori in New Zealand a couple of centuries ago. Ordinarily, the speakers of English imposed their vocabulary on the Māori community. Crucial in this article is the phonological adaptation of English words into Māori, with special attention paid to the simplification of consonant clusters. This process is occasionally far from straightforward, especially when two or three English consonants in a row require phonological reinterpretation. Moreover, this paper is in line with the recent views that what happens in adaptation need not always be phonological. On the other hand, the apparently dominated linguistic community has found a way to influence New Zealand English vowels and contribute a few lexical items to that language. This paper also proposes a diagram in which the vowels of Māori are represented on the Cardinal Vowel Scale.

Keywords: consonant group decomposition; Māori; New Zealand English; Cardinal Vowels; svarabhakti

Streszczenie

Artykuł ma na celu zapoznanie czytelników ze związkiem języka maoryskiego z angielszczyzną dominującą w Nowej Zelandii. Inne wybrane języki orientalne już częściowo zanalizowałem w ramach teorii fonologii rządu. Język maoryski jest typowy dla odmian pacyficznych, ma jednak dość odmienną specyfikę. Spółgłosek jest tu niewiele, gdyż ten język nie toleruje klasterów, a więc angielskie zbitki w zapożyczeniach muszą ulec dezintegracji, która miewa uzasadnienie fonologiczne. Należy także zauważyć, że nie wszystkie zmiany językowe mają charakter fonologiczny. Proponuję również nową prezentację schematu samogłosek maoryskich i odświeżenie postrzegania nowozelandzkich.

Słowa kluczowe: maoryski; angielski nowozelandzki; dekompozycja spółgłosek; svarabhakti; samogłoski kardynalne

This paper primarily analyzes phonological interfaces between English and Māori. It should be clarified at the outset that English spoken in New Zealand now is no longer British English, and contemporary Māori is not the same as it was when English commenced to be the dominant system. Their contact has been manifold, and this paper examines how they have interacted phonologically and lexically. Many English words have been adapted by Māori users, while Māori’s influence on New Zealand English has also been significant over the past decades.

First, the paper will present Māori and its phonology, accompanied by examples of Māori words in New Zealand English (NZE). Second, NZE will be presented with a view to understanding why its vowels are now so different from those of standard English. Subsequently, the analysis will move on to Māori loanword adaptation from English and the disintegration of original consonant clusters from the perspective of Government Phonology. The paper will seek if phonology can always provide explanations for word-adaptation issues. Finally, conclusions will be drawn. All transcriptions are based on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Austronesian languages have a reputation of having very few consonants and vowels compared to many Western sound systems. John Lynch1 classifies Māori, also known as Te reo Māori, as a Proto Central-Eastern Polynesian language, a branch of Austronesian, and further places it into the Central subgroup along with Hawaiian, noting its more southern position. According to Ray Harlow,2 Māori – the indigenous tongue of New Zealand (called Aotearoa in Māori) – is an Eastern Polynesian language, belonging to the Tahitic subgroup. It is spoken by about 17% of the population of New Zealand.3 Its history is complicated, and a detailed account is beyond the scope of this analysis. What matters is that, since the arrival of Dutch and, later, English (18th century), Māori has adopted huge numbers of loanwords which have contributed to enriching its vocabulary. Its phonology has not changed radically since the time it was described in the 1950s and 1960s.4 Even so, the quality and quantity of the linguistic descriptions have improved over the past few decades.

Before detailing of phonological systems of Māori and NZE and their

interactions, it should be noted that numerous Māori words in general

use are utilized in NZE nowadays. The most common ones are shown

below:5

(1)

aroha – ‘love’,6 hangi – ‘traditional feast prepared in earth oven’, iwi – ‘tribe’, kai – ‘food’, Kia ora –‘hello, greetings’, kiwi – ‘native flightless bird’, makō – ‘shortfin shark’, mana – ‘prestige, reputation’, Māori – ‘indigenous inhabitant/language of New Zealand’, Pākeha – ‘New Zealander of non-Māori descent’, tapu – ‘taboo, secret’, Te Reo Māori – ‘The Māori language’, whanau [fanau] – ‘family’

This is but a handful of examples of words which both the natives of Māori and the speakers of NZE use on a daily basis. Note that some lexical items from that region, such as kiwi, have gained worldwide popularity. Another example is the word taboo, coming from Proto-Oceanic *tabu and Proto-Polynesian *tapu, which is identical to the form of the word in Māori.7 Although the interactions between the vocabularies of both Māori and NZE are not exactly proportional, the native lexical items of Aotearoa have not been completely eliminated and are even occasionally preferred.

Paul Warren and Laurie Bauer8 as well as R. Harlow9 describe the system of Māori as follows. First, it is a (C)V language, i.e., every syllable must have a vowel (a melodically realized nucleus), while consonants (onsets) are normally optional. Hence, no consonant clusters are allowed.

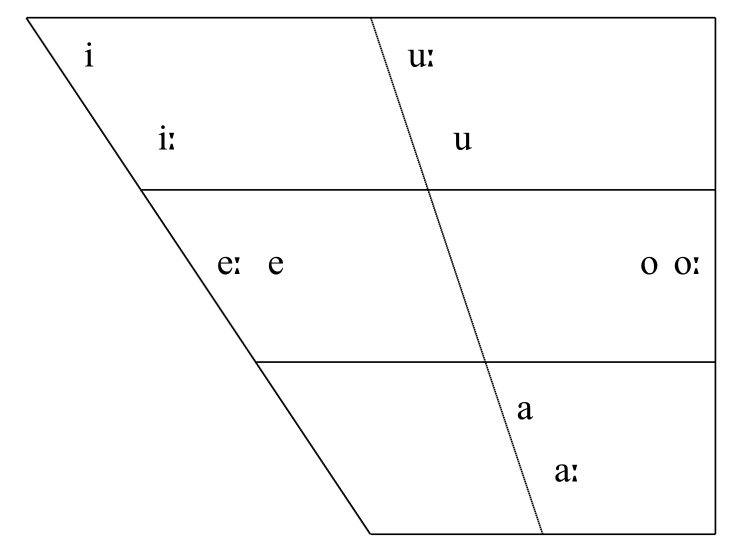

Regarding the vowels, the Māori system is relatively straightforward. It has the typical five vowels, i.e. /i, e, a, o, u/, either long or short. The contemporary spelling practice is intended to reflect the phonological reality of this tongue. Specifically, the macron above the long vowels is very important to the users of Māori. It is also worth noting that there are a few diphthongs in this language. These are not a focus of this paper, though.

In the globally accessible literature, a Cardinal Vowel

Scale (CVS) chart of Māori vowels does not appear to be

available.10

However, on the basis of Harlow’s formant frequencies measured

in speakers born in the 1970s, the following diagram can be

proposed:11

(2) Māori vowels on CVS

As shown above, there are no typical corner vowels in the system of Māori, bar the short /i/, and no vowel symbol is placed on the edges of the chart. There is only one truly back vowel here, i.e. /oː/. Thus, the speakers prefer front or central vowels.

As for the consonants, they are unremarkable from the viewpoint of the Austronesian group and are also unsophisticated. The inventory includes only three voiceless unaspirated plosives /p, t, k/, two fricatives /f, h/, three nasals /m, n, ŋ/, one liquid /r/ and one glide /w/. Dialectal and even idiolectal variation is common, the velar nasal is spelled with ng, while the fricative /f/ or /ɸ/, is represented by wh. The liquid is phonetically [ɾ] in most cases.12

To realize in what linguistic surroundings Māori is used by some speakers in New Zealand, it is helpful to present the variant of English spoken therein. Although the consonants of NZE do not differ much from their Received Pronunciation (RP) counterparts, the vocalic system requires some comment in terms of IPA symbolism:13

|

|

NZE |

RP |

| short vowels |

/ɘ, e, ɛ, ɐ, ɒ, ʊ/ |

/ɪ, e, æ, ʌ, ɒ, ʊ/ |

| long monophthongs |

/iː, ɐː, oː, ʉː, ɵː/ |

/iː, ɑː, ɔː, uː, ɜː/ |

|

diphthongs |

/æe, ɑe, oe, æʉ, ɐʉ, iə, eə, ʉə/ |

/eɪ, aɪ, ɔɪ, aʊ, əʊ, ɪə, eə, ʊə/ |

|

unstressed short vowels |

/ɘ, i/ (and /ɯ/ before final sonorants) |

/ə, i/ (and /ə/ before final sonorants) |

|

|

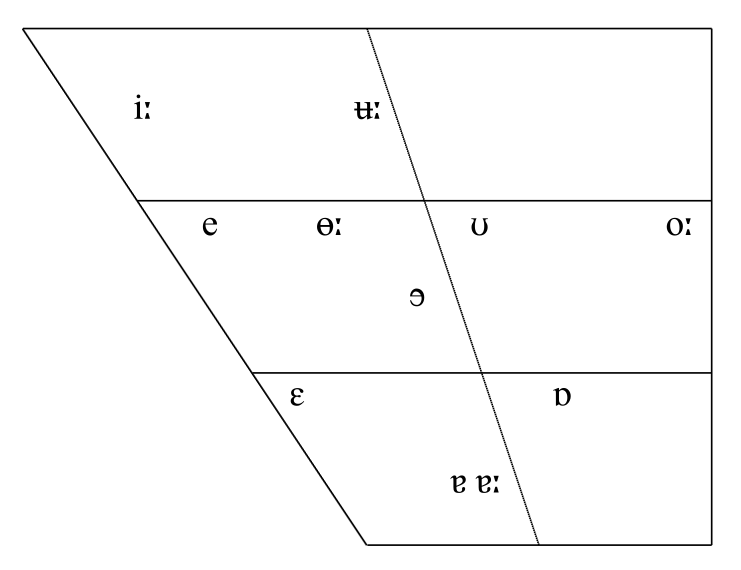

The following figure, representing the NZE vowels on the CVS, is based on

P. Warren.14

The range of phonetic realizations may vary, depending on sex and age.

(3) NZE vowels on CVS

Phonetically, a few sounds seem more surprising than others, considering the short vowels, e.g., /ɘ/, which is centralized and lowered, as a version of the RP /ɪ/. A variety of English without a short i-like vowel is unusual. I question the proposed quality of the short /e/. Having heard a few speakers of NZE,15 I would suggest that their /e/ is much higher than that of RP and slightly higher than cardinal vowel number 2. I would call this sound an advanced /ɪ/. Secondly, the RP ‘ash’ vowel is raised to /ɛ/, the short /ɒ/ is higher and fronted, while the short /ʊ/ is lowered and centralized. As to the long vowels, the /ʉː/ is centralized and lowered, the long ‘schwa’ higher and fronted, while /ɐː/ is higher and central. Overall, the NZE speakers tend to avoid truly back vowels, with the exception of /oː/. Besides, in RP English, five vowels are located on the edges of the CVS, namely /e/, /æ/, /ɑː/, /ɒ/ and /ɔː/, while in NZE there is a supposedly one, i.e. /oː/.

Summing up, the set of developments shown above suggest a ‘Little Vowel Shift’ in NZE relative to RP.

This raises the question of why NZE vowels are so fronted or centralized relative to RP vocalic sounds. When comparing the charts in (2) and (3) above, a possible hypothesis emerges. Specifically, given that the English-speaking Kiwis have been linguistically separated from their mother tongue in its British form for over two centuries, it is likely that their vocalic inventory has been continuously influenced by that of Māori.16

As regards the interchange of vowels of both systems, these sounds have little influence on syllable structure and they simply provide the nuclei, whose phonetic shape depends on the perception of the vowels from the donor language. The 12-vowel system of English (without diphthongs) is reduced to 10, with vowel length being debatable. The solutions are clear in the light of the above-mentioned charts and the following examples.

As to the consonants at hand, numerous changes can be observed. As shown by Marta

Degani,17

the consonants from NZE (24 items) are interpreted in Māori in the following

way (with a few amendments):

(4) NZE Māori

/p, b, f/ > /p/

/t, d, s, z, ʒ, ʃ/ > /t, h/

/k, g/ > /k/

/tʃ, dʒ/ > /h, r/

/θ, ð/ > /t/

/m, n, ŋ/ > /m, n, ŋ/18

/l, r/ > /r/

/v, w/ > /w/

/j/ > /i/ ?

Several parts of this are of interest. Since Māori does not tolerate voiced obstruents, the English voiced plosives /b, d, g/ consistently undergo devoicing. The affricates undergo serious modifications – they are realized as a fricative or a liquid. The fricatives are either demoted to stops on the scale of sonority, e.g., /f/ to /p/ or /θ, ð/ to /t/, or promoted to the liquid, i.e., /r/.19 The sibilant /s/ seems especially alienated in Māori. As will be shown below, this sound is consistently adapted and is easily replaced by /h/, e.g., huka – ‘sugar’ (word-initial), or pahi – ‘bus’ (word-medial). However, when it occurs in original clusters, it is deleted in Māori. It is also worth noting that the original /f/ followed by a vowel is retained and spelled as wh, e.g., whutupōro ‘football’.20 The nasals, as a group, are the only survivors. Therefore, out of 24 consonant phonemes in RP or NZE, Māori retains fewer than a half.

Several perspectives must be considered in the procedures of borrowing words from a donor/source/L1 language to a borrower/target/L2 system. Apart from purely phonological changes, which are L1 > L2, with slight amendments, there are also approaches that assume other factors. Einar Haugen (1950) pioneers the study of word adaptation as a linguistic phenomenon in general.21 As for phonology and phonetics, Michael Kenstowicz22 highlights the role of perception, while Allison Adler23 maintains that sticking to the speakers’ own systems (faithfulness) and individual mindsets (perception) may be crucial, in addition to phonological patterns. It seems, however, that Jolanta Szpyra-Kozłowska24 summarizes all of the above intra-linguistic and extra-linguistic reasons in the most comprehensive manner. Complex issues appear to be reducible to three main factors: orthography, phonology and perception (both orthographic and aural, resulting in expected and unexpected outcomes).

Degani25 mentions a few repair strategies or adaptation methods by which Māori adapts the influx of words from English. The ones which could be treated phonologically include direct integration, insertion of final vowels, substitution of absent consonant sounds, reduction of consonant clusters, epenthesis in consonant clusters, reduplication,26 metathesis, etc.

Direct integration is a phenomenon about which there is nothing new to write, e.g., [pea] for ‘pair’. Reduplication, quite common since Ancient Greek, involves repetitions of morphemes or lexemes, e.g., pukapuka (‘book’). All of these can be narrowed down to only one structural change in a CV language: all onsets need phonetically realized following nuclei, with the phonemic substitutions being a marginal issue in structural terms. Such an approach might seem simplistic. The focus of this analysis, however, is how the L1 consonant clusters are reflected in L2 in terms of both phonology and other aspects.

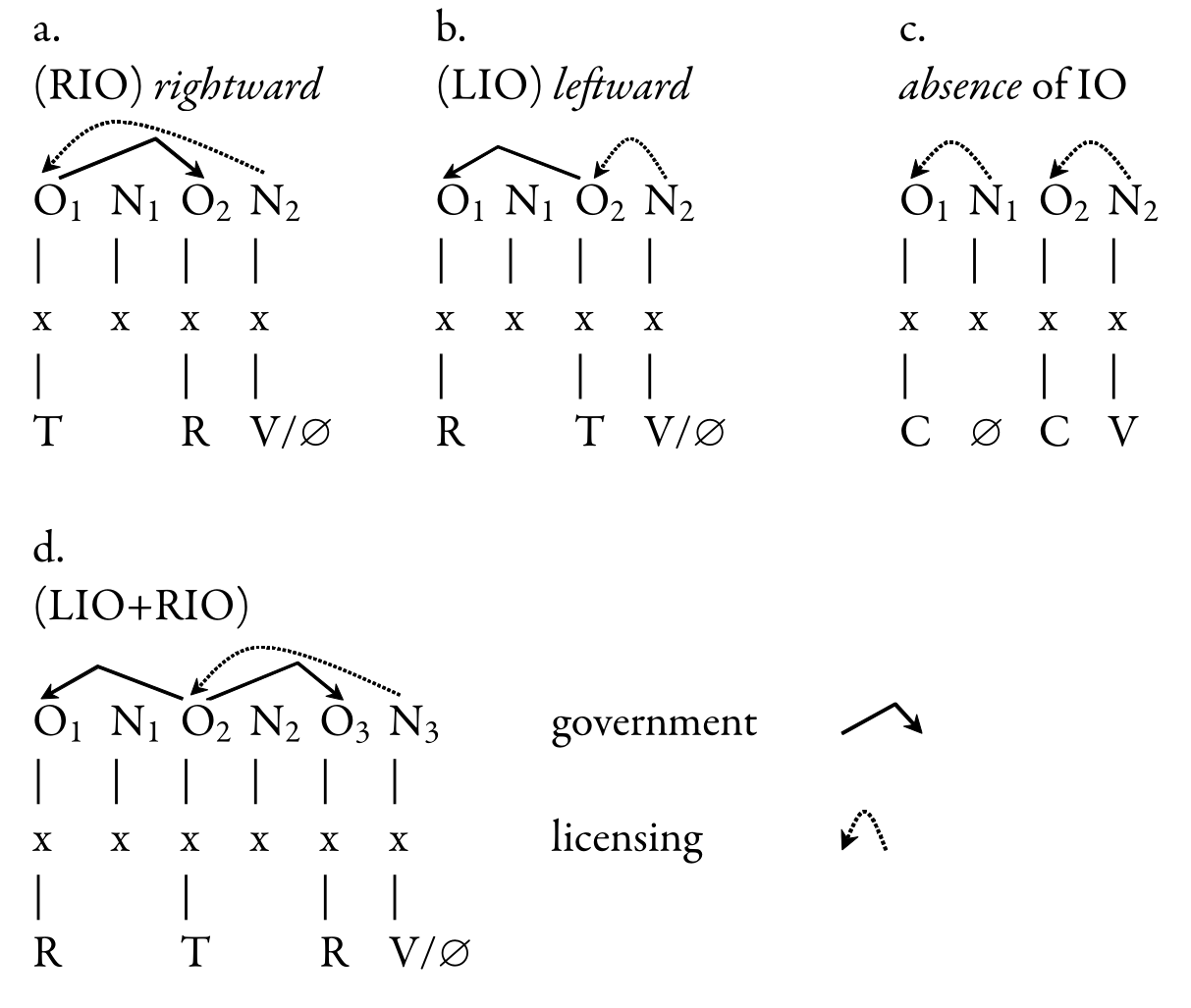

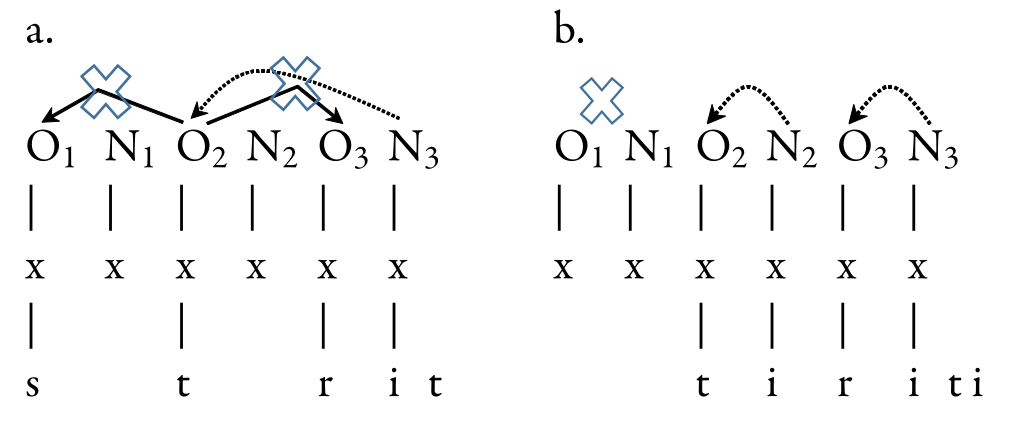

Here, the basics of Government Phonology27 or, more precisely, its recent version called Complexity Scales and Licensing28 are presented. The whole theory is based on minimalistic assumptions that there is asymmetry in phonology, and that relations between segments in a phonological string are local and directional. In the CSL model, the only two constituents, i.e. onsets and nuclei, never branch. Obstruents (governors) govern sonorants (governees).29 Every nucleus licenses the preceding onset. Governing relationships hold between onsets and are referred to as inter-onset (IO) relations. These are government-licensed by the nuclei that follow such domains. There are two possibilities depicted below, namely LIO – left inter-onset, and RIO – right inter-onset domains. Typical ‘branching onsets’ are RIO structures, while geminates, partial geminates and ordinary clusters, previously treated as ‘coda-onset’ groups, belong to LIO. RIOs are cross-linguistically more difficult to government-license, as they are further away from the government-licensing nuclei. LIOs are easier to support by such nuclei and, as such, they are universally more common. Below, (T) stands for ‘obstruent’, (R) for ‘resonant’, (V) for ‘vowel’, (∅) for ‘empty nucleus’, while (C) represents ‘any consonant’:

(5)

Although the model has been present in the literature for a long time, a word should be said about the nuclei without melodic content. In both (5a) and (5b) the nuclei (N1) are present in the structure only formally,30 i.e., they are locked and licensed by RIO or LIO to remain silent. Thus, the clusters in these structures are true. In (5c), on the other hand, the empty nucleus (N1) has a role to perform. Its function is to license the preceding onset. If that does not happen, it should manifest itself as a vowel. Thus, the clusters in such situations are spurious. Given that (N1) in (5a) and (5b) are locked by IO relations, these IO domains are government-licensed by (N2). Figure (5d) illustrates a complex situation – a combination of (5b) and (5a) – with the same requirements and solutions. As previously stated, RIO in (5a) is a more difficult structure to government-license, while LIO in (5b) is easier. Both situations reflect the distance between the government-licensing nuclei and the governors. The easiest configuration to maintain is a simple CVCV sequence in (5c).

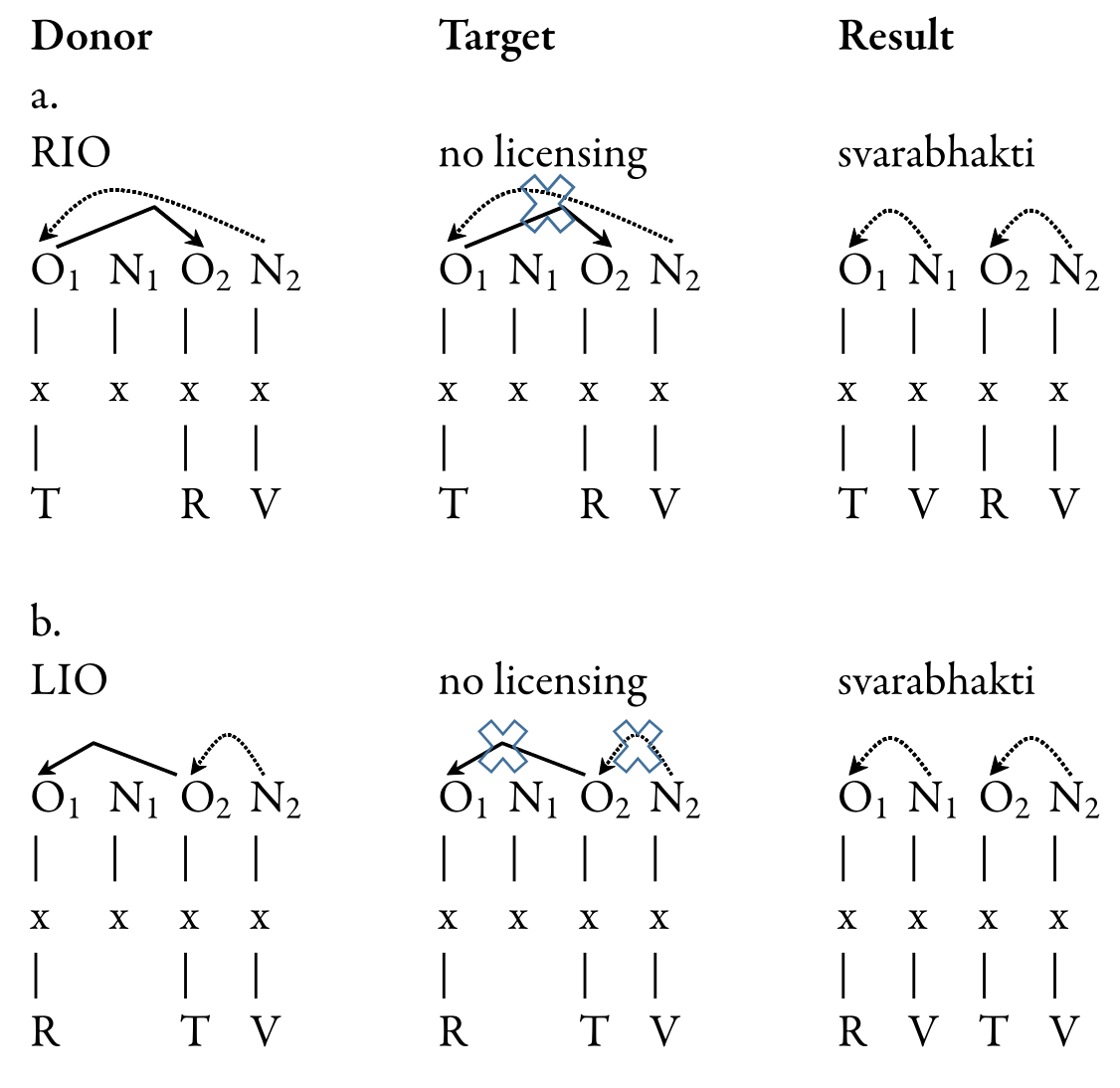

Differences in these structures between languages which enter L1–L2 relationships may result in complications and reconfigurations. Regarding repair strategies in loanword adaptation, a few possibilities can be proposed for languages which do not tolerate consonant groups. Most of these involve vowel epenthesis/svarabhakti:

(6)31

As presented above, the mechanism is simple. As there are no consonant clusters in L2, every group needs to be broken up with a vowel. In terms of government-licensing, nuclei do not provide enough power to the obstruents to govern the sonorants. The lack of both licensing types is represented by saltires. Thus, vowel epenthesis is common. As for the LIO+RIO combination depicted in (5d), the same procedure should be applied and result in double epenthesis. This is what happens in borrowed words, e.g., in Japanese, where the English word stress is realized as [sɯtoɾesɯ].

The data illustrating Māori borrowings from English are divided according to

cluster types and their position in L1 words (IPA). The symbol (V) represents

a svarabhakti vowel.

(7)

a. TR clusters (initial and medial)32

[pl] play > [pVrV] purei

[pr] priest > [pVrV] piriti or pirihi (probably dialectal)

[bl] blue > [pVrV] purū-pōuri (reduplication, just idiosyncrasy)

[br] bridge > [pVrV] piriti

[tr] truck > [tVrV] taraka

[dr] drive(r) > [tVrV] taraiwa

[kl] clock > [kVrV] karaka

[kr] cream > [kVrV] kirīmi

[gl] glass > [kVrV] karāhe

[gr] grass > [kVrV] karaehe

[gr] group > [rV] rōpu (inconsistent with the previous entry)

[fl] flour > [pVrV] pāraoa

[fr] frog > [pVrV] poraka

[sl] slate > [tVrV] terete (inconsistent, /s/ should be /h/)

[sn] snake > [nVkV] neke (inconsistent, /s/ is deleted)

b. [s]+T(R) clusters (initial and medial)

[sp] spade > [pV] pēti

[st] stool > [tV] tūru

[st] history > [tV] hītōria

[sk] school > [kV] kura

[sk] whisky > [hVkV] wihikē

[spr] spring > [pVrV] piringa

[str] street > [tVrV] tiriti

[skr] scribe > [kVrV] karaipi

c. RT clusters (medial and final)

[mp] champion > [mVpV] tiamupiana

[mb] number > [mV] nama (inconsistent with [4] above, the stop is deleted)

[nt] paint > [VtV] peita (inconsistent, the nasal is deleted)

[ŋk] monkey > [VkV] maki or makimaki (reduplication, inconsistent, the nasal is gone)

[ŋ(g)] spring > [VŋV] piringa (debatable, is it [ŋg] or [ŋ+g]?)

[nθ] panther > [nVtV] panata

[nʤ] angel > [nVhV] anahera

[lk] milk > [rVkV] miraka

[lf] golf > [rVfV] korowha (most probably, a re-borrowing from Dutch)

d. other medial clusters

[kt] doctor > [kVtV] tākuta

[kʧ] picture > [kVtV] pikitia

[pt] captain > [pVnV] kāpene or ketene (inconsistent, /t/ or /p/ is removed)

[tb] football > [tVpV] whutupōro

[kf] breakfast > [kVhV] parakuihi (inconsistent with [4], /f/ should be /p/)

It goes without saying that one cannot gather all the possible donor language clusters, since not all of them occur in Māori loanwords.33 The clusters, of all types, are obligatorily split with vowels.

However, some inconsistencies also require attention. The original group /gr/ is either turned into /kVr/, i.e. grass > karaehe, which is in line with the general pattern, but it may also drop the [g] in another example, i.e. group in (7a). In such a case, this can be described as a perceptual reinterpretation. This phenomenon is particularly evident in /s/+C clusters in (7b). Māori users ‘refuse’ to observe its presence in the original English words across the board, except for whisky, where both L1 obstruents, i.e., /s/ and /k/, are present, with the natural amendments done in L2, i.e., epenthesis and the change of /s/ to /h/. /s/ is replaced by /t/ in slate (7a), but not in snake, which appears to be another perceptional idiosyncrasy. In (7c) both a pattern and a few peculiarities can be observed. The pattern works for liquids followed by obstruents and nasals followed by non-homorganic fricatives and affricates. It does not for homorganic nasal-stop groups. Such a picture is far from what normally occurs cross-linguistically. This issue will be returned to later on.

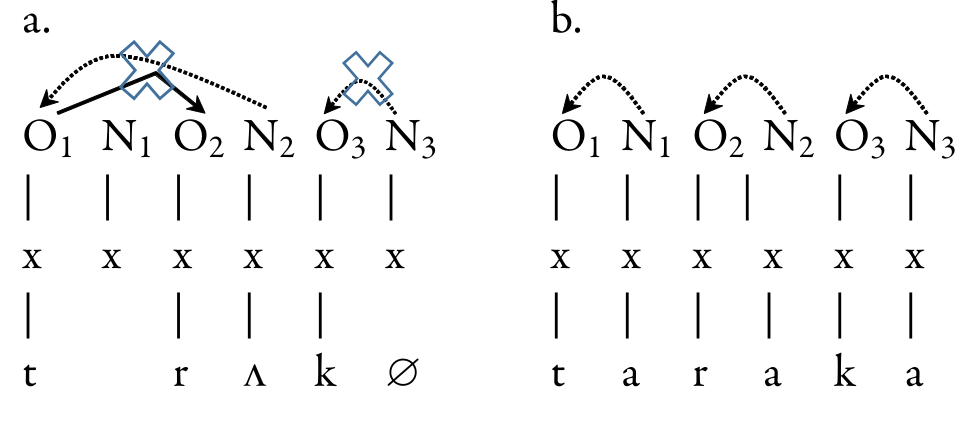

This section presents a GP analysis of the adaptation of the English consonant

clusters into Māori. The first example, representing TR groups, is truck >

taraka.

(8)

In (8a), (N2) fails to provide government-licensing to (O1). Hence, epenthesis occurs in (N1). Analogically, the original empty nucleus (N3) is too weak to support (O3), with the natural consequence being its filling with melody. These outcomes are illustrated in (8b).

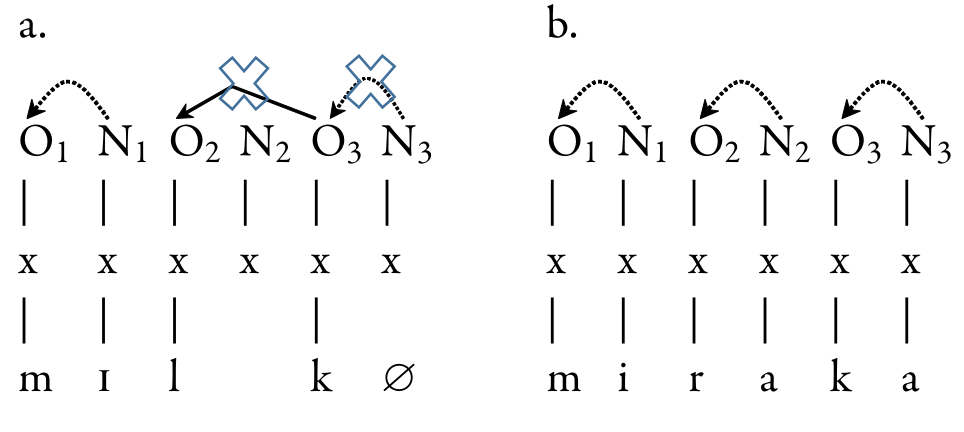

Next, the analysis turns to what often happens in English RT consonant

groups, e.g. milk > miraka.

(9)

In (9a) the IO government in the cluster /lk/ is not supported by (N3). Thus, double epenthesis is observed in (N2) and (N3) in (9b).

More interesting are the examples involving the spirant /s/ followed by a stop (and a liquid or glide). Consider the development of street > tiriti below.34

(10)

In (10a), a complex governing domain is shown which involves both LIO and RIO. Due to the fact that Māori nuclei, even if filled with melody, are very weak regarding both licensing and government-licensing, these IO relations are broken up. Svarabhakti under (N2) is regular. However, a similar process, which might be expected in (N1), does not occur. More striking is the fact that both (O1) and (N1) in (10b) are treated as non-existent, i.e. they are in fact removed from the structure of the word. A similar phenomenon can be observed in simpler clusters, e.g. /sp/ in spade > pēti, or /sk/ in school > kura.

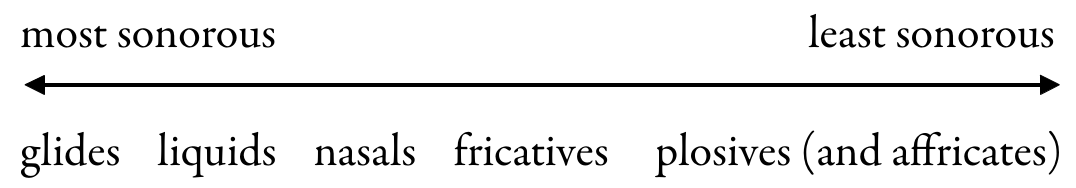

The analysis above shows, then, that regular TR and RT clusters from

English are treated as CVCV structures, with widespread svarabhakti vowels.

However, such expected adaptations occur only if the cluster members in L1 are

composed of segments which are perception-wise quite diverse from each other.

Specifically, /t/ and /r/ in truck as well as /l/ and /k/ in milk are highly

distinct, i.e., these are stops and liquids which are placed far away from each

other on the commonly accepted sonority hierarchy/ scale (consonants

only):

(11)

Conversely, in (7b) there are also clusters composed of /s/+C, e.g. school, and /s/+TR in street, in which the initial /s/ is completely erased from Māori. This may be understandable in terms of the universal sonority sequencing proposed by Elizabeth Selkirk.35 Specifically, sonority should rise towards the nucleus and fall from the nucleus, which is confirmed by the afore-mentioned cases. Definitely, in /s/+C clusters, there is no sonority rise, and languages in which such groups are licit are more complex than Māori. Thus, the Māori system prohibits three ON sequences in a row. In a CVCV language, however, this constraint is expected. Moreover, in (7c) there are even more surprising reinterpretations of homorganic nasal+stop groups in which only one segment apparently ‘wins’ and survives in Māori. Herein, sonority falls from the nucleus, but the distance between the nasal and the plosive is not so great.

As for the sounds which should be reflected but are not in Māori, e.g., why school is adapted as kura but not as *hukura, the phenomenon may be seen as dialectal or preferential. In other words, phonology may have little to say here. Allison Adler36 suggests, regarding a similar Pacific language, i.e., Hawaiian, that remaining faithful to one’s own phonological system may take precedence. In the inventory of Hawaiian, many speakers do not perceive differences between, e.g., /sp/ and /p/, or /sk/ and /k/. If individual language users happen to be influential, the whole community may take over the recommended perceptions or interpretations. While the exact historical process is unknown, her analysis must rely on speculation. What seems to be obvious, though, is that it falls beyond the scope of a purely phonological analysis.

In Māori, given spade or school, the community may not perceive /s/ as a single sound, or as a phoneme. Its members may be of the opinion that, since /s/ is not ‘their own’ speech sound, it should be treated as a part of other obstruents in the immediate neighborhood, perhaps a sort of unnecessary pre-aspiration, which is known from some Western tongues,37 and which has no impact on the native sound system. Thus, they may be of the same view as the Hawaiians, i.e., /sp/ and the like are simply /p/ sounds. The speakers are truly faithful to their own system principles. Consistency is another matter. For example, if /s/ is followed by sonorants in L1, it may be replaced by /t/, e.g. slate > terete, or deleted, e.g. snake > neke. Thus, /s/+T results in a loss, while /s/+R is open to reinterpretation. For some users, sonorants may pattern with obstruents, while other users draw a line between the two major groups of consonants.

However, what should be done about homorganic nasal+stop groups, e.g. paint > peita? What happens to the L1 plosives? Regarding European-African-Asian interactions, most speakers of these broadly understood linguistic communities recognize such clusters. Thus, /mp, mb, nt, nd, ŋk, ŋg/ are present in English, Spanish, Polish, Tamil or Japanese, as well as in most Bantu languages. In language adaptation, there are no issues regarding these clusters.

In Māori, this is not the case, and number is pronounced as nama, while monkey is realized as maki. This raises the question of what makes Māori even less tolerant of these clusters.

The reasons may be based on perception and interpretation again. Peter Ladefoged and Ian Maddieson38 mention languages such as Sinhala (Sri Lanka) and Fula (West and Central Africa), where the so-called pre-nasalized stops can be heard. Apart from clusters such as /m+b/, /n+d/, ŋ+g/, they display segments like /mb/, /nd/ and /ŋg/. These languages have complex consonant inventories. No such contrasts are found in Māori.

For the sake of argument, three simplified systems can be visualized in which

there are nasal+stop groups. The first is based on English, the second on

Sinhala:

(12)

English Sinhala possible Māori interpretation39

/mb/ /mb/ and /mb/ /m/ or /b/

/nd/ /nd/ and /nd/ /n/ or /d/

The complexity of nasal+stop groups, which is diverse in languages having rich inventories of consonants and their possible clusters, may lead to drastic reductions in extremely simplex systems. Thus, adaptation is a complicated matter, and one cannot rely on phonology alone.

The foregoing investigation has shown that the Māori vocalic system may have had an influence on that of NZE, especially in terms of advancing English back vowels on the CVS. Besides, the lexicon of NZE has been enriched by a few Māori words.

Next, a GP analysis of consonant cluster decomposition from English to Māori has been offered. Using the concepts of licensing and government, it has been shown that Māori nuclei are too weak to support consonants in terms of government-licensing. As for the CV structure, Māori users seem stable in that they insert vowels between the clusters in initial and medial parts of words, and word-finally. On the other hand, their interpretation of the L1 input may vary, depending on dialectal factors or the variable influence of certain speakers, especially if the L1 /s/ sound is involved. It has also been proposed that the total deletion of /s/ may reveal a perceptional factor, which has little to do with phonology. It manifests itself in the treatment of [s] as a part of other obstruent phonemes in the immediate phonetic neighborhood, which leads to the truncation of whole onset-nucleus sequences.

In Māori, the situation is more complicated, as homorganic nasal+plosive groups from L1 are reinterpreted as reduced to one out of two melodies, e.g., paint > peita, or rephrased as two distinctive sounds in, e.g. champion > tiamupiana, where both /m/ and /p/ are present in L2.

In summary, loanword phonology seems to be an easy procedure in languages whose sound systems are comparable. When it comes to a clash of systems in which sound inventories are poles apart, other factors come into play. As already said, phonology should come first, but faithfulness to the native tongue, resistance to L1 and reinterpretation, not always linguistically logical, may play great roles. In the case of Māori, its system seems to be the most resistant to changes among the comparable Pacific languages I have analyzed so far.

Literature

Adler A.N., Faithfulness and Perception in Loanword Adaptation: A Case Study from Hawaiian, “Lingua,” 116 (2006), no. 7, pp. 1024–1045, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2005.06.007.

Bauer L., Warren P., New Zealand English: Phonology, in: A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, eds. E.W. Schneider et al., Berlin–New York 2004, pp. 580–602.

Bauer L. et al., Illustrations of the IPA: New Zealand English. “Journal of the International Phonetic Association,” 37 (2007), no. 1, pp. 97–102, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100306002830.

Cyran E., Complexity Scales and Licensing in Phonology, Berlin 2010.

Degani M., Language Contact in New Zealand: A Focus on English Lexical Borrowings in Māori. “Academic Journal of Modern Philology,” 1 (2012), pp. 13–24.

Elbert S.H., Pukui M.K., Hawaiian Grammar, Honolulu 1979.

Gordon E., Maclagan M., Regional and Social Differences in New Zealand: Phonology, in: A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, eds. E.W. Schneider et al., Berlin–New York 2004, pp. 603–613.

Gussmann E., Phonology: Analysis and Theory, Cambridge 2002.

Harlow R., Consonant Dissimilation in Māori, in: Currents in Pacific Linguistics: Papers on Austronesian Languages and Ethnolinguistics in Honour of George W. Grace, ed. R.A. Blust, Canberra 1991, pp. 117–128.

Harlow R., Māori: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge 2006.

Haugen E., The Analysis of Linguistic Borrowing, “Language,” 26 (1950), pp. 210–331, https://doi.org/10.2307/410058.

Herd J., Loanword Adaptation and the Evaluation of Similarity, “Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics,” 24 (2005), pp. 65–116.

Jaskuła K., Levels of Interpretation in Sound Systems, Lublin 2014.

Jaskuła K., A New Consonant-Vowel Architecture: Japanese Borrowings from European Languages from the Viewpoint of Complexity Scales and Licensing, “Lingua Posnaniensis,” 65 (2023), no. 1, pp. 49–70, https://doi.org/10.14746/linpo.2023.65.1.3.

Jaskuła K., Phonotactic Adaptation of English Loanwords in Hawaiian: A Government Phonology Approach to Consonant Cluster Decomposition, in: Phonology, Its Faces and Interfaces, eds. J. Szpyra-Kozłowska, E. Cyran, Frankfurt am Main 2016, pp. 257–275.

Jones, A.M., Phonetics of the Māori Language, “The Journal of the Polynesian Society,” 62 (1953), no. 3, pp. 237–241.

Jones D., An English Pronouncing Dictionary, London 1917.

Kaye J., Lowenstamm J., Vergnaud J.-R., Constituent Structure and Government in Phonology, “Phonology,” 7 (1990), pp. 193–231, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952675700001184.

Keegan P.J., Teaching of Māori Language Pronunciation Based on Research and Speech Analysis, “Te Reo – The Journal of the Linguistic Society of New Zealand,” 66 (2024), issue 2 (special issue), pp. 57–73.

Kenstowicz M., The Role of Perception in Loanword Phonology, “Studies in African Linguistics,” 32 (2003), no. 1, pp. 95–112.

Krupa V., The Māori Language, Moscow 1968.

Labrune L., The Phonology of Japanese, Oxford 2012.

Ladefoged P., Maddieson I., The Sounds of the World’s Languages, Cambridge, MA 1996.

Lowenstamm J., CV as the Only Syllable Type, in: Current Trends in Phonology: Models and Methods, eds. J. Durand, B. Laks, Salford–Manchester 1996, pp. 419–441.

Lynch J., Pacific Languages: An Introduction, Honolulu 1998.

Macalister J., The Changing Use of Māori Words in New Zealand English, “New Zealand English Journal,” 14 (2000), pp. 41–47.

Selkirk E.O., The Syllable, in: The Structure of Phonological Representations, Part II, eds. H. van der Hulst, N. Smith, Dordrecht 1982, pp. 337–383.

Szpyra-Kozłowska J., Perception? Orthography? Phonology? Conflicting Forces Behind the Adaptation of English /ɪ/ in Loanwords into Polish, “Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics,” 52 (2016), no. 1, pp. 511–549, https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2016-0001.

Warren P., Quality and Quantity in New Zealand English Vowel Contrasts, “Journal of the International Phonetic Association,” 48 (2018), no. 3, pp. 305–330, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100317000329.

Warren P., Bauer L., Māori English: Phonology, in: A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, eds. E.W. Schneider et al., Berlin–New York 2004, pp. 614–624.

Internet sources

100 Words in Te Reo Māori, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/maori-language-week/100-maori-words [access: 12.03.2025].

Māori Words Used in New Zealand English, https://www.maorilanguage.net/maori-words-phrases/maori-words-used-new-zealand-english/ [access: 14.03. 2025].

Origin and History of taboo, https://www.etymonline.com/word/taboo [access: 17.02.2025].

Te Aka Māori Dictionary, https://maoridictionary.co.nz/ [access: 14.01.2025].

1 J. Lynch, Pacific Languages: An Introduction, Honolulu 1998.

2 R. Harlow, Māori: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge 2006, pp. 10–14.

3 P.J. Keegan, Teaching of Māori Language Pronunciation Based on Research and Speech Analysis, “Te Reo – The Journal of the Linguistic Society of New Zealand,” 66 (2024), issue 2 (special issue), pp. 57–73.

4 A.M. Jones, Phonetics of the Māori Language, “The Journal of the Polynesian Society,” 62 (1953), no. 3, pp. 237–241; V. Krupa, The Māori Language, Moscow 1968.

5 Māori Words Used in New Zealand English, https://www.maorilanguage.net/maori-words-phrases/maori-words-used-new-zealand-english/ [access: 14.03.2025]; 100 Words in Te Reo Māori, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/maori-language-week/100-maori-words [access: 12.03.2025].

6 A comparison can be made with the world-famous Hawaiian aloha. Hawaiian does not have [r], while Māori lacks [l], the connection being more than obvious.

7 Origin and History of taboo, https://www.etymonline.com/word/taboo [access: 17.02.2025].

8 P. Warren, L. Bauer, Māori English: Phonology, in: A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, eds. E.W. Schneider et al., Berlin–New York 2004, pp. 614–624.

9 R. Harlow, Māori: A Linguistic Introduction, pp. 62–70.

10 The CVS is a trapezium for extreme vowel production proposed by Daniel Jones, An English Pronouncing Dictionary, London 1917. Available also on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6UIAe4p2I74.

11 R. Harlow, Māori: A Linguistic Introduction, p. 81.

12 A.M. Jones, Phonetics of the Māori Language, p. 239; J. Herd, Loanword Adaptation and the Evaluation of Similarity, “Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics,” 24 (2005), p. 101; R. Harlow, Māori: A Linguistic Introduction, pp. 75ff.

13 L. Bauer, P. Warren, New Zealand English: Phonology, in: A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, eds. E.W. Schneider et al., Berlin–New York 2004, pp. 580–602; L. Bauer et al., Illustrations of the IPA: New Zealand English, “Journal of the International Phonetic Association,” 37 (2007), no. 1, pp. 97–102, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100306002830.

14 P. Warren, Quality and Quantity in New Zealand English Vowel Contrasts, “Journal of the International Phonetic Association,” 48 (2018), no. 3, p. 306, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100317000329.

15 E.g., television series such as The Brokenwood Mysteries and The Gone, and numerous internet videos. Moreover, Kiwi is not perceived an offensive term to English-based speakers.

16 For details of pronouncing Māori words in NZE as well as dialectal variation, see also: L. Bauer, P. Warren, New Zealand English: Phonology, pp. 597ff.; J. Macalister, The Changing Use of Māori Words in New Zealand English, “New Zealand English Journal,” 14 (2000), pp. 41–47; E. Gordon, M. Maclagan, Regional and Social Differences in New Zealand: Phonology, in: A Handbook of Varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, eds. E.W. Schneider et al., Berlin–New York 2004, pp. 603–613.

17 M. Degani, Language Contact in New Zealand: A Focus on English Lexical Borrowings in Māori, “Academic Journal of Modern Philology,” 1 (2012), p. 18.

18 See below regarding [ŋ].

19 It is worth mentioning that there is only one liquid here, just like in, e.g., Hawaiian (see S.H. Elbert, M.K. Pukui, Hawaiian Grammar, Honolulu 1979) and Japanese (see L. Labrune, The Phonology of Japanese, Oxford 2012).

20 There are also inconsistencies, e.g., whoroa ‘floor’ vs. pāraoa ‘flour’, perhaps to avoid homophony. However, homophones are not unwelcome. Other irregularities will be mentioned where relevant.

21 E. Haugen, The Analysis of Linguistic Borrowing, “Language,” 26 (1950), pp. 210–331, https://doi.org/10.2307/410058.

22 M. Kenstowicz, The Role of Perception in Loanword Phonology, “Studies in African Linguistics,” 32 (2004), no. 1, pp. 95–112.

23 A.N. Adler, Faithfulness and Perception in Loanword Adaptation: A Case Study from Hawaiian, “Lingua,” 116 (2006), no. 7, pp. 1024–1045, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2005.06.007.

24 J. Szpyra-Kozłowska, Perception? Orthography? Phonology? Conflicting Forces Behind the Adaptation of English /ɪ/ in Loanwords into Polish, “Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics,” 52 (2016), no. 1, pp. 511–549, https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2016-0001.

25 M. Degani, Language Contact in New Zealand, pp. 19–20.

26 Reduplication is well described in, e.g., R. Harlow, Consonant Dissimilation in Māori, in: Currents in Pacific Linguistics: Papers on Austronesian Languages and Ethnolinguistics in Honour of George W. Grace, ed. R.A. Blust, Canberra 1991, pp. 117–128.

27 J. Kaye, J. Lowenstamm, J.-R. Vergnaud, Constituent Structure and Government in Phonology, “Phonology,” 7 (1990), pp. 193–231, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952675700001184.

28 E. Cyran, Complexity Scales and Licensing in Phonology, Berlin 2010. This model is a development of J. Lowenstamm, CV as the Only Syllable Type, in: Current Trends in Phonology: Models and Methods, eds. J. Durand, B. Laks, Manchester 1996, pp. 419–441.

29 When there is a sonority plateau situation, the ‘coda’ position consonant is treated as R.

30 See also, E. Gussmann, Phonology: Analysis and Theory, Cambridge 2002, pp. 70–71.

31 K. Jaskuła, Levels of Interpretation in Sound Systems, Lublin 2014, pp. 119–120; K. Jaskuła, Phonotactic Adaptation of English Loanwords in Hawaiian: A Government Phonology Approach to Consonant Cluster Decomposition, in: Phonology, Its Faces and Interfaces, eds. J. Szpyra-Kozłowska, E. Cyran, Frankfurt am Main 2016, pp. 252–253; K. Jaskuła, A New Consonant-Vowel Architecture: Japanese Borrowings from European Languages from the Viewpoint of Complexity Scales and Licensing, “Lingua Posnaniensis,” 65 (2023), no. 1, pp. 54–55, https://doi.org/10.14746/linpo.2023.65.1.3.

32 As can be seen, the second part of the original group normally surfaces as the phonemic liquid /r/. Although it may be a phonetic tap [ɾ], this does not always happen, so we will adhere to the phonemic symbol here.

33 The present data come from the sources mentioned above as well as from Te Aka Māori Dictionary https://maoridictionary.co.nz/ [access: 14.01.2025].

34 For the sake of simplicity, we hereby ignore the fact that the vowel in street is long.

35 E.O. Selkirk, The Syllable, in: The Structure of Phonological Pepresentations, Part II, eds. H. van der Hulst, N. Smith, Dordrecht 1982, pp. 337–383.

36 A.N. Adler, Faithfulness and Perception in Loanword Adaptation, pp. 1024–1045.

37 See, e.g., Icelandic preaspiration in E. Gussmann, Phonology: Analysis and Theory, pp. 54–59.

38 P. Ladefoged, I. Maddieson, The Sounds of the World’s Languages, Cambridge, MA 1996, pp. 119–123.

39 This is not to say that Māori borrows from Sinhala.